I will be writing about the entire plot of The Voyage Out in

this post, so if you haven’t read it and don’t want any spoilers please save

this post for another time!

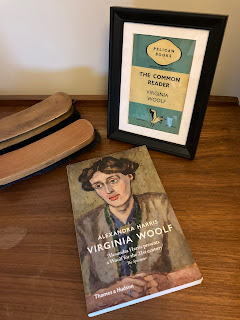

I have just finished reading The Voyage Out for the second

time and only five years since I first started it! Interestingly, The Voyage

Out was first published in 1915, so I have finished it 100 years after it was

written. Virginia Woolf started writing

this book around 1910 and got married to Leonard Woolf in 1912, half way through

writing it, so it has taken me the same amount of time to read and write about

it as it took her to write the whole book!

I was born 100 years after Virginia Woolf, so it is very

easy to see myself in her shoes 100 years on. In 2015 I live alone in a house

that I am paying the mortgage for and live in a world with so many more choices

but also some of the same struggles. It

might just be that I am reading lots about the choice or women to marry or not,

and facing those questions in my own life, but I really found this book to be

an exploration of what it means to a woman to get married (or not) and how big

a decision in your life that can be.

A quick plot summary

The central character of this book is Rachel Vinrace, her

mother died when she was eleven and she was brought up by her father and her

aunts in Richmond. Now, aged 24, she is setting off on a voyage to South

America on her father’s ship with her aunt and uncle (her mother’s younger

brother.) Her aunt is shocked to learn of the sheltered life she has been

living. Rachel has never been kissed and has no idea about men or sex. Her aunt

Helen takes her under her wing and starts to educate her in life and encourages

her to think for herself and form her own opinions of the world. Her voyage

into womanhood begins on her father’s ship when she is kissed by the married

Richard Dalloway, unlocking a whole new world to her. Once she has arrived in

South America she meets two men, Hewet and Hirst, who along with Helen continue

to challenge her assumptions about life and what it means to be a woman. After

many conversations Hewet and Rachel are engaed to be married. But their happy

little life in England will never happen as Rachel develops a fever and dies.

Women

The first thing that struck me about the book was that the

central characters were almost exclusively women and the male characters were

mostly on the edge of the action, making a comment here or there but largely

remaining silent (Ambrose) or absent (Willoughby). The only men to get any real

attention are Hewet and Hirst, the love interest and his friend. The other thing that struck me about all

these women is that they represent the variety of choices in life that a woman

could make at that time:

Helen Ambrose – wife, and mother, intelligent, inquisitive

and bold

Mrs Thornbury – married, lots of children, probably anti-suffrage

Mrs Elliot – married and very conventional but childless

(not through choice)

Mrs Flushing – married, eccentric upper class

Miss Allan – a spinster, more interested in her work than

married life

Susan Warrington – on the path to becoming a spinster but

now engaged

Evelen M – not sure that she wants to get married at all and

would rather conquer the world.

Rachel Vinrance – our heroine, 24, never been kissed, naive

about the world but curious and full of excitement.

The lower classes don’t really get a mention! We have a

small glimpse into the life of Emma Chailey when we see her room on the boat

out, but otherwise we know very little about her or any of the other servants.

I think that Woolf uses these women to explore the choices

that women have about their lives, how they might feel about them and the

sacrifices they have to make that just don’t apply to men in the same way.

I was also struck that the Dalloway’s feature in The Voyage

Out. The pompous Richard Dalloway, his character made me really angry. I don’t

know if this is the same Richard and Clarissa Dalloway of Mrs Dalloway, but I

like to think of Woolf having all of those characters with her for years before

they come out on the page. In The Voyage Out the Dalloway’s join the ship part

way through the voyage and Richard reveals a whole new part of the world to

Rachel. Whilst the rest of the ship are taken out with sea sickness Richard and

Rachel talk together before he kisses her and then blames her for doing it

saying “you tempt me”!!!

The difference

between men and women

St John Hirst discusses with Rachel the reasons why women

might be different to men

“It’s actually difficult to tell about women, how much I

mean is due to lack of training, and how much is native incapacity... you’ve

led an absurd life until now.”

St John Hirst seems to want women to be his equal, his

friendship with Helen and her liking of him is very important

“Few things at the present time mattered more than the

enlightenment of women.”

It’s odd to think that this was written at a time when women

didn’t have the vote and the suffrage movement was in full swing. There are

some interesting observations about the impact of women achieving the vote

which were very perceptive. Hewett remarks that

“It’ll take at least six generations before you’re

sufficiently thick skinned to go into law courts and business offices. Consider

what a bully the ordinary man is, the ordinary hard working, rather ambitious

solicitor or man of business with a family to bring up and a certain position

to maintain. And then, of course, the daughters have to give way to the sons,

the sons have to be educated; they have to bully and slave, for their wives and

families and so it all comes over again. And meanwhile there are the women in

the background.”

Woolf asserted that it would take 6 generations for this

problem to be solved. 100 years later we are only 4 generations on and the place

of women in the workplace (or lack of), particularly in more senior roles is

still very relevant today. We’ve made huge progress in terms of women’s rights

in the last 100 years but there is still a long way to go. I’ve just finished

reading

Lean In by Sheryl Sandberg and in

it she talks about both the environment of the office and the role of men in

providing for their families. She suggests that until it is completely accepted

that the role in the home is just as important as the work outside of the home,

and men play an equal role in this, then women won’t be able to achieve

equality in the workplace.

Where are all the

women?

Woolf also makes an observation about the fact that the

lives of women generally go unrecorded in the history books. There is a long

passage by Hewett about how men never properly record women’s history and women

don’t have a voice either

“of course, we’re always writing about women – abusing them,

or jeering at them or worshipping them, but it’s never come from women

themselves. It’s the man’s view that’s represented you see... Doesn’t it make

your blood boil? If I were a woman I’d blow someone’s brains out. Don’t you

laugh at us a great deal? Don’t you think it all a great humbug?”

Again, this still rings true today. I am slowly discovering

more and more women who have seemingly vanished from the history books. Where

growing up I assume that very few women were able to achieve great things, I am

now discovering that their achievements have been hidden and lost to history.

Take the photographer

Gerda Taro, she worked with Robert Capa (indeed some of his photos may

have been taken by her) but her name is not as well recorded. She was killed

during the Spanish civil war and her achievements were lost, unlike Robert Capa

who when he died was immortalized in numerous books and exhibitions. Or Lee

Miller, (who is now getting more recognition, there is an exhibition at the

ImperialWar Museum at the moment) who too was an incredible photographer in her

day, establishing new photography techniques that Man Ray took all the credit

for, she is recorded as his lover. Her work fell into obscurity until her son

discovered all of her negatives after his parent’s death and he has now made

sure her achievements are remembered.

The BBC has just produced a four part documentary called

The Ascent of Woman which

looks at the history of women in the development of the world and in particular

focuses on how their stories have been lost, forgotten or retold to minimize

their achievements.

Will you marry me?

The main theme of the book seems to be marriage and challenging

the idea that his is what people should do. Evelyn M is an interesting

character as she seems to challenge the idea of marriage entirely.

“Just because one’s interested and likes to be friends with

men, and talked to them as one talks to women, one’s called a flirt.”

She has a proposal of marriage from two men and rather than

worrying about which one to accept she is more concerned that she was asked in

the first place and doesn’t quite know how to say no to either of them. She

admires Garibaldi and other great explorers and I think she would rather

explore the world than settle down. Hewet says

“the women he most admired and knew best were unmarried

women. Marriage seemed to be worse for them that it was for men.”

Again it is interesting that 100 years on the ideas and views of marriage

haven’t changed a great deal. Although now couples can live together, marry and

divorce with little comment from others, and with access to contraception

marriage doesn’t mean a family of thirteen children, it is still very much seen

as the done thing.

Spinster

by Kate Bollick which has just been published in the UK this year examines the

single life through the eyes of five female authors and explores how marriage

(or not marrying) affected them and their work, as well as exploring what it

means to be a spinster in 2015.

Towards the end of the book Evelyn sums up her feelings

about marriage and how it is not for her

“Love was all very well,... but the real things were surely

the things that happened in the great world outside, and went on independently

of these women.”

The life that Evelyn wants is very reminiscent of the life

Virginia and her siblings were leading, she wants to be able to meet with other

people and discuss the world

“A nice room in Bloomsbury preferably where they could meet

once a week.”

Till death us do part

The death of Rachel is really the death of an alternative

way of living married life together to that of previous generations. Hewett was

insistent that in their marriage Rachel would be free to be herself and that

they would be happy together. Does the fact that Rachel dies suggest that Woolf

didn’t think that this was a possibility? One thing that stuck out when I read

this passage when Rachel dies is what Hewett says immediately following her

death

“No two people have ever been so happy as we have been.”

This is very similar to the words Virginia used in her letter

Leonard before she took her own life in 1941. You can see a copy of the letter

and a transcript

here

I saw the letter at the National Portrait Gallery exhibition

about Woolf in 2014 and it was incredibly moving to read.

It seems odd that she wrote almost the same thing 26 years

later to describe her life with Leonard in the same way as she had written

about two characters in her first novel. Leonard must really have made her very

happy.