|

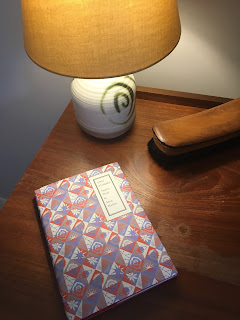

| Two Stories 100th anniversary edition published 2017 |

Two Stories was published in 1917 and was the first publication printed by the Hogarth Press. I saw the actual Hogarth press a few years ago when I visited Sissinghurst and was taken back by how manual this process must have been. We take for granted now how easy it is to print a document but setting the type by hand and printing each page is a very labour-intensive process, something we just don’t think about. I’ve wondered before what Virginia would have made of digital technology in relation to publishing. Would she have written a blog? Or had an Instagram account? Her work challenged what a novel needed to look like, I’m sure she would have been influenced by the impact that new technology had on how we chose to tell stories.

Like most of the books I’ve read, I wasn’t sure what to expect from this story and it went into a completely different direction than I expected it. Like many of Virginia Woolf’s short stories, this book is something of a sketch. A moment on a cold evening where she observes the objects around her and allows her thoughts to drift to new ideas.

As with all the books, I’m reading in this project. I’ve tried not to find out too much about them so that my first read is entirely shaped by my own experience, rather than preconceived ideas and yet I’m still surprised by what each story has to offer and how unlike what I think of Woolf to be. The melancholy and illness she experienced loom large over my impression of her, and yet so much of her writing is about the joy and privilege of life. Yes, it is intense, thought-provoking, and challenging, but there is also something about the vastness of the world and what it means to be alive that makes her work very uplifting.

Two stories was the first book Virginia and Leonard published on the Hogarth press. They literally set the type and printed the pages themselves. They made 134 copies which required over “4000 pulls on the printer on Leonard’s part” and it was sold to their network of friends. It was the start of the Hogarth press as a publisher, which is still in existence today. Both Leonard and Virginia wrote a story, and they were printed alongside woodcuts created by their friend, Dora Carrington.

I read The Mark on the Wall several times because, although it is the shortest of stories, at just 23 small pages, there is so much packed into each sentence and on so many levels

The following section contains spoilers

On the surface, the story is the wandering thoughts of the narrator who is sat in front of a fire on a January afternoon. Their musings on life are interrupted when they notice a mark on the wall “7 inches above the mantelpiece.” Rather than get up to see what it is. They contemplate what it could be from their seat. As they do this, their thoughts flit from topic to topic. These few moments on a sunny afternoon, letting their thoughts wander, take us through hundreds of years of history and they contemplate how the world might be significantly changed in the years to come.

The last page is a jolt into reality “curse this war” when you realise that these moments of daydream have been an escape from the horror of the war, that would’ve filled the newspapers every day. This piece was written in 1917. The great war was raging in Europe, and it was a time of huge social change. The war and the flu epidemic of 1918 caused huge numbers of death which led to societal change. Women would begin to get the vote in 1918, although not all women, and changes in class, art and literature all occurred. I think Woolf sensed that change was on the way and being able to print her own work opened up a freedom to write what she wanted. Without the restriction of a publisher. She talks about the “intoxicating sense of illegitimate freedom that could come from the letting go of old conventions in society.”

And then the story ends with the light-hearted realisation that the mark on the wall is in fact, a snail, which is accompanied by a lovely woodcut illustration.

The more I read the story the more I see themes of what Woolf will write about in the coming years, challenging convention, both in society, and in the field of novel writing. You can also see how she reflects on the role of women in the world, and of course, a stream of consciousness style of writing, where authors of the future will be “leaving the description of reality, more and more out of their stories.”

The book was originally published alongside a story by Leonard Woolf called Three Jews. Unsurprisingly I don’t have one of the 134 hand printed editions, although you can see one at the The British Library here. The edition I have read was published by Hogarth, who are part of Penguin Random House, in 2017 celebrating 100 years since the original publication of the book. The Leonard story has been bumped for a new story called St Brides Bay, by Mark Haddon, who is a fan of Virginia Woolf. He also created a linocut of Virginia Woolf to compliment Carrington’s linocuts in the original edition.

I really enjoyed The Mark on The Wall, possibly my favourite thing I have read so far, and I’m delighted that I have a Mark on My wall that mentions this piece

|

| Woodcut from 2008 to celebrate the 10th Anniversary of the Virginia Woolf Society of Great Britain. |